-

- Lynn Conway's

Retrospective

- Lynn Conway [Update of 2-25-09.]

- Copyright © 1999-2003,

Lynn Conway.

- All Rights

Reserved.

-

-

-

-

- PART III: STARTING

OVER

-

Starting over - - "going stealth" - - - settling down

in my new life - - - making new friends - - - dating men and

having fun - - the effect of the gender transformation is almost

like a miracle to me - - - I can finally just be myself, in a

body that feels great to be in, and openly love and be loved

simply for who I am - -

-

- Some nice career successes occur at Memorex - - I begin working

as a computer architect again - - - ah, but then project cancellation

- - - time to make a big career decision - - - great fortune

at joining PARC - - then amazingly - - - being mentored by Bert

Sutherland - - - meeting Ivan Sutherland, Carver Mead - - - getting

involved in some of the most exciting research going on in computing

at the time - - seeing an opportunity for creating new design

methods - - - innovating the VLSI system design methods - - -

creating a paradigm-shifting VLSI systems textbook - - - getting

bolder and more confident in my career, and taking many daring

steps along the way - - - and by ten years after my transformation,

I'm suddenly on the threshold of career fame - - whether I'm

ready for that, is another question - - - because I must live

in "stealth mode", and have to worry about losing my

career opportunities if I were ever publicly outed - -

-

-

- You miss 100 percent of the shots you never take

-

- - Wayne Gretzky

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- The best way to predict the future is to invent

it -

- Alan Kay

-

-

-

- 5. STARTING ALL OVER AGAIN:

-

- - - - The late 60's were a remarkable time of new opportunities

for women - - - the 50's seemed like a distant past - - - many

companies were trying to bring many more women into regular professional

positions that had previously been predominantly male-only -

- - the period of quotas and affirmative action hadn't arrived

yet, so there wasn't much backlash from men - - - after all the

numbers of women in most places was still small - - - however,

the opportunities were there at just the right time for me -

- - especially in the then wide-open field of computer programming

- - - in fact, many of the new computer programmers were women

who learned their skills "on the job", much as the

early webdesigners did in the 90's - - -

-

- - - - it was in this dramatically changed context for women

at work that I got my first job as a woman at CAI as a programmer

- - - a number of other young women had also recently been hired

by CAI, and we all became good friends - - - this was great,

because it gave me a chance to immediately build a circle of

regular gals as friends and buddies - - - for socializing, shopping,

and having fun together - - - and this helped me stabilize my

life a lot and quickly reduced my feelings of loneliness - -

-

-

- - - - I worked on one timesharing project at CAI, learning

about time-sharing operating systems on the job, and making some

useful contributions by figuring out why their stuff wasn't working

right - - - once I was making some money again - - - I had moved

from San Francisco to a tiny one-room apartment down on the Peninsula

in Sunnyvale, and re-entered "the real world" as Lynn

Conway - - -

-

- - - - CAI was a good stepping stone - - - I was soon recruited

with several other women programmers from CAI to go work at Greyhound

Time-Sharing (GTS), which was just starting up - - one of my

programmer friends at work named Cindy and I decided to get an

apartment together as roomates - - - Cindy was a very beautiful,

friendly, fun-loving gal and we hit it off great together - -

- we found a really nice two-bedroom apartment on Middlefield

Road in Mountain View, where we lived together for a couple of

years - - - it was a new complex with nice grounds and a swimming

pool - - - it felt really great to be in decent housing again

- - -

-

- GTS was folded later that summer by the parent company, but

they were good about it, and we were given some time to look

for new jobs this was a huge scare for me - - - I thought good

grief, if I can't find a job again, I'm going to lose out after

all - - - however, the timing turned out to be quite expedient

- - - my headhunter put me onto to a really good job at Memorex

Corporation, which I landed in September 1969 - - - finally the

darkest days of my early life were now over, and the sun was

about to shine a little! - - -

-

-

- Memorex Corporation

-

- - - - In 1969, memorex was an exciting start-up that had

"gone critical" and become a substantial force in the

IBM compatible disc-drive business - - they would soon even enter

the computer business (small business systems) - - there seemed

to be possibilities for an exciting future there - - - although

I didn't go into a lot of detail about my work at IBM, my background

in system architecture, digital design and simulation work gave

me a lot of credibility with the hiring managers and personnel

people - - and I got a good offer from them - -

-

- - - - and the offer was still there after I informed the

personnel department of my medical history, and showed them full

documentation regarding what had been done, including a copy

of Dr.

Julian Pichel's Psychiatric Report - - - that independant

psychiatric examination by someone not involved in my case management,

and which was supportive without hesistation, was very useful

in making the case - - besides, no one at Memorex expressed anything

remotely like the concerns that the IBM corporate folks had obsessed

about just the year before - - -

-

- - - - these were younger folks in a recent start-up company

- - - folks who had met me personally, and who simply listened

carefully to my detailed explanation of what had happened to

me - - - they were used to making up their own minds about things,

rather than relying on prevailing prejudgments - - - so I joined

Memorex - - - and was soon to begin a really good job, in a really

good company - - -

-

-

- Restarting my engineering

career and my social life

-

- - - - but basically, I had to start all over again - - -

for one thing, the IBM-ACS project had been so secret that the

project itself didn't have an identity among engineers in the

valley, much less any work that I'd done there - - - and there

wasn't much I could say about what I'd done at IBM anyways, for

fear of revealing my gender transition - - - then too, I needed

to develop a wide range of new hands-on technical skills in order

to work within the fast-paced, start-up type of environment -

- - so I had to start all over pretty much from scratch technically,

and prove myself all over again, first as a systems programmer,

then moving on to work as a digital designer and computer engineer,

and then finally getting a chance to work on computer architecture

again - - -

-

- - - - this wasn't easy and was sometimes pretty scary - -

even though I'd had some realistic social and medical/physical

experiences when I was 20-22 years old, I was now experiencing

a complete and profound new internal and external reality, going

through what amounts to a "second puberty" - - by now

the overall transformation was bringing on a deluge of new experiences

at work, and especially in my personal life and in my own internal

physical perceptions and emotional experiences - -

-

- - - then, in 1970-71, the case of April

Ashley broke into the news - - April was a beautiful English

socialite who had been a famous model in the early 60's and who

had then married a prominent peer - - however, she had been born

a boy from a poor family, and had worked as a female impersonator

at Le Carrousel in Paris - - - she had become one of Georges

Burou's earliest patients (I understand she was SRS number 6

by Dr Burou in Casablanca on May 12, 1960), and thus was among

the first tiny band of transsexual women to undergo modern "sex-change"

surgery - - - see

recent news article about April - -

-

- - - living in stealth mode, April was "outed" in

1970, and her husband's wealthy family forced the case into the

divorce courts where the marriage was declared invalid - - the

courts even declared that April was "still a man" since

she was XY genetically. This case set a disastrous precedent

that has affected post-op women in the UK ever since (they are

considered by the legal system there to be males, and cannot

marry "another man") - - and it terribly frightened

me - - - the idea of being "outed" and somehow declared

to "be a man" was an unthinkable thing to be avoided

at all costs - - so for the following 30 years I almost never

talked about my past to anyone other than close friends and a

few lovers - - -

-

- - - - by '70 I'd only just begun to make some new friends

- - - and although I had a few friends to socialize with and

gain emotional support from, I still felt withdrawels and loneliness

and alienation from the huge transition I'd just gone through

- - - I also missed seeing my little girls a lot, but tried not

to think about this if at all possible - - - I also found myself

slipping in and out of bouts with shyness and social withdrawal

because of my terrible fears of being outed - - - however, I

worked very, very hard at getting things going, while trying

not to make too many mistakes - -

-

- - - - having Cindy for a roomate was wonderful, because we

could go shopping, go out socializing, and do a lot of fun things

together - - - she helped me grow out of my shyness more and

more - - - and within a couple of years after SRS, I was settling

into my new life pretty comfortably - -

-

- - - - my career also took a great turn for the better when

in '71, after a successing of increasingly more responsible positions

at Memorex, I was selected as processor architect for a new small

business computer system - - the Memorex 30 - - -

-

-

- The Memorex 7100 Processor

-

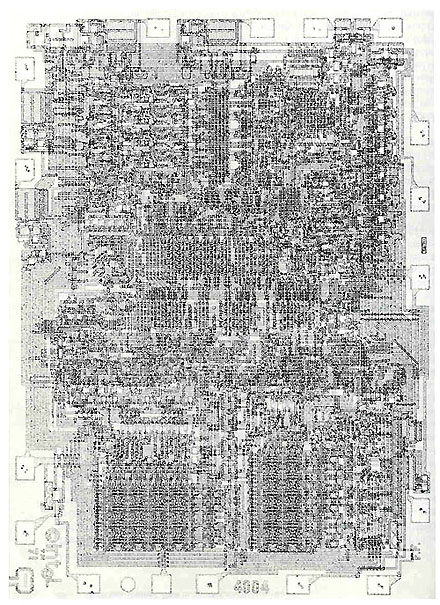

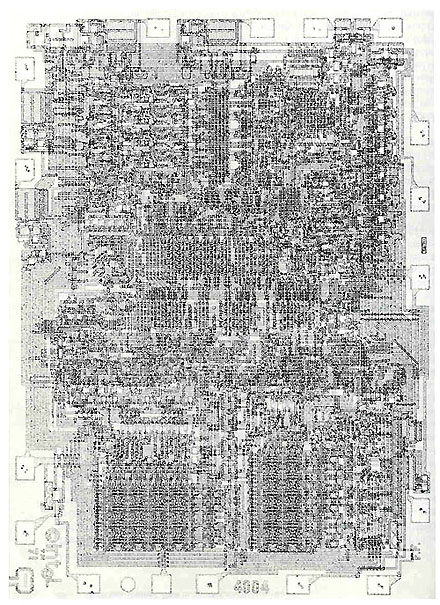

- - - - the Memorex 7100 processor for Memorex 30 System, a

new low-end model for Memorex's line of computers - - - aimed

at competing with IBM's System 3 - - -

-

- - - - Milt Gregory pulled together and led the matrixed project

team - - - the fast development cycle - - my initial architectural

ideas - - this was to be a lean, mean, low-cost, no-frills machine

- - - the use of a simulator to cohere the design - - our effort

to get on top of all the newest parts due out from various suppliers

- - - in 9 months we went from blank piece of paper to a working

manufacturing prototype - - a microprogrammed processor in TTL

technology - -

-

- The Memorex 30 Team:

-

- Milt Gregory, Anthony J "Tony" Miller, Lynn Conway, Roger Stallman, Gary

Yee, Bob Peterson, Al Hemel, Dick Hoenle, Bob Holland, Don Pesavento,

Glenn Ewart, Dick Chueh and Barbara Baird.

-

-

- - - - this project developed into a wonderful group experience

- - with a great bunch of people who were fun to work with, and

who were really sweet to me - - - I learned a lot on this project

about hands-on engineering of real products - - what the digital

designer's life in the trenches was really like - - - and I really

enjoyed the exciting team-effort aspect of the project - - -

Milt was a great leader, and I learned a lot about team leadership

by watching how he did things - - - also, late in the effort,

the team worked with Barb Baird to produce a manual documenting

the design - - fortunately, I still have a copy - - -

Update of 2-25-09: I've just scanned and posted the Memorex 7100 System

Reference Manual online. You'll find PDF's of the complete manual and separate

chapters at the following links:

Memorex 7100 System Reference Manual,

Front-matter,

Introduction,

System Architecture,

CPU Architecture and

Microprogramming, CPU

Logic Design, Memory

System,

System

Control and Display Panel,

I/O System,

Physical Description,

Power Supply,

OPSYS1 Emulation Package,

MRX30

Emulation and Performance,

MRX30 Phase

"0" Cost Estimate.

-

-

-

-

- - - at this point, things were going great - - I was making

excellent money, and was accepted as a senior technical peer

by leading engineers in the company - - - I'd also gained confidence

as a technical project leader, while guiding the processor development

portion of the overall project - - - and in 1971 I was promoted

to Senior Staff Engineer - -

-

-

- Having Fun

-

- - - - I bought a nice little condo in Los Gatos in '72 -

- - conveniently located at 420

Alberto Way (#25), near to downtown - - - by now my past

troubles had sort of melted away, and my inner perceptual, emotional

and physical setting had settled down and stabilized into its

wonderful new form - - - I'd also made significant gains in social

adventurousness, and was freely enjoying an active social life

- - - I traded in my old Volkswagen Beetle on a new '72 Datsun

240Z - - - it was red with a white interior; what a car! - -

- that thing helped propel me further into some wonderful new

experiences - - -

-

-

- Lynn's Datsun 240Z in front of

her condo building, in 1972.

-

-

- - - - I loved dancing to rock & roll, rhythm & blues,

and country music at the roadhouses like "Cowtown"

down in San Jose - - - and barhopping in general - - - I was

now dating men regularly - - I got started by frequenting the

various singles bars and by using the then-new "computer

dating services" - - - and from time to time I began having

really wild fun - - the surgery had finally released me to fully

enjoy lovemaking - - I could wrap my legs around a man and make

love with wild abandon - - without elaborate preparations, without

fear, shame or embarrassment, and without hiding anything - -

- and my body was now beautifully soft and rubbery, and sweetly

sensitive and responsive to a man's touch, due to the female

hormones - - - my god, what joy this brought me - - -

-

- - - - I also now had two

beautiful Siamese cats , Samantha and Rapunzel - - I've always

loved cats, and these two sweet little critters were to be my

faithful companions for many, many years into the future (Sams

lived to be 21 and Punzel lived to age 23!) - - -

-

- From this point on, my personal life was much like that of

any other single woman in her mid-thirties, full of the same

challenges and rewards that lively women of that age experience.

For many years I dated regularly, and usually had a couple of

somewhat steady boyfriends with whom to share interests and have

fun - - - here are some photos from this period:

-

|

- Lynn in her

- '72 Datsun 240-Z

-

- 1973

|

-

-

|

Lynn at a car show

1973 |

-

-

|

Lynn's roomate Cindy

1971 |

-

-

-

- The 4004 Appears

-

- - - in 1971 something very significant happened in the valley

- - - the Intel 4004 appeared and soon began to get into all

sorts of applications - - a blockbuster event for digital system

designers - - I talked to anybody who knew anything about it

- - took short intensive courses at Santa Clara University -

- tried to find out what was going on - - the processor was very

simple architecturally - - - but the design details and process

were very unclear - - do architects have to know anything about

LSI to do this stuff? - - apparently not - - it's a big team

effort involving architects, logic designers, circuit designers

and layout designers - - - it's complex and costly to design,

even for such a simple processor? - - - but makes sense if there's

lots of applications because it's so inexpensive to replicate

- - -

-

-

|

Photomicrograph of the Intel

4004 chip - the first microprocessor |

|

-

-

- Project Cancellation

-

- - - - but then there are rumblings - - business problems

- - - gads, the MRX 30 project is canceled! - - - not only that,

but Memorex announces that it's getting out of the computer business

- - - this was a terrible disappointment - - I felt like I had

the flu for the next month - - - now what to do? - - - we went

into hold mode for a while, and then there were layoffs - - I

survived those, but finally couldn't see a future at Memorex

- -

-

- What Next?

-

- - - What to do? - - - I had to get a grip on things and decide

what to do next - - - I finally signed up a headhunter and went

looking for a microprocessor to architect! - - heck, why not?

- - there were very few folks in the valley at the time who knew

how to do computer architecture - - - so I'd guessed that those

architects already doing the microprocessors didn't know much

about the underlying technology either - - -

-

- - - - this proved to be a good guess - - - I interviewed

with and got a great offer from Fairchild - - - but then my headhunter

mentioned that Xerox had started a new research outfit in Palo

Alto that might be interesting - - I went to check it out - -

- I could hardly believe what I saw on that interview trip -

- PARC in 1973 was already an astounding place - - the mission

- - the people - - the computing environment - - the special

feeling of a different, exotic technical culture - - - I got

an excellent offer from Xerox - - - and the offer was still on

the table after I'd fully informed the personnel manager about

my past history, using all my medical documentation plus Dr.

Pichel's Report - - -

-

- Note: By 1973,

transsexualism was much more widely known about than in '68,

especially in the Bay Area. In the five years since I'd been

fired by IBM, Dr. Benjamin's book had had a great impact in the

medical community. Stanford University Medical Center in particular

had started an exploratory program in the late 60's to evaluate

transsexual cases and to develop standard protocols for treatment.

The program resulted from knowledge of successful cases, including

mine, that Dr. Benjamin had diagnosed and then guided on through

SRS and transition in the 60's.

-

- Back in 1968, I'd been among the first few

hundred U. S. citizens to undergo SRS, and almost all of them

had gone abroad for their surgery. The majority were entertainers,

sex-trade workers, and others who could pass and find marginal

work as women back then. That's why there hadn't been any precedents

for IBM's corporate response to my transition. Such a thing just

hadn't happened before in IBM, or in any other major corporation

that they knew about, and there was no script for handling the

situation.

-

- However, during the late 60's as Dr. Benjamin's

work became known, many more transsexuals sought medical help.

According to Dr. Benjamin, by 1973 almost 2500 Americans had

undergone the change - - - and with each passing year a higher

percentage were educated and professional women who were able

to maintain some degree of career success afterwards - - - by

then the Stanford efforts were generally known about by the public

in the Bay Area, having received occasional news attention -

- this started to open folks minds to the idea that there was

a rare gender-transition disorder that an elite organization

such as Stanford took seriously, and wanted to study and help

- - - it's possible that this Stanford involvement in treatment

of transsexuals helped sway the Xerox personnel department in

my favor during the hiring process there - - - I kept in touch

with Dr. Benjamin for many years after my transition, usually

seeing him for a lunch or dinner at least once each summer when

he was in San Francisco. It was wonderful to be able to share

in his happiness in knowing that his work was having a lot of

impact and helping many desperate people, and that he would eventually

be recognized as an great medical pioneer.

-

- - - - I did get another big scare during

the summer of '76 when Renee

Richards, a then recently post-op transsexual, was "outed"

by national media (her story is documented in her '83 book, Second Serve).

A huge controversy raged about her playing in tennis competitions

as a woman, and people made fun of her as they had of Christine

Jorgensen years before - - - even more so in Richard's case because

she was very strange-looking (unfortunately for her she had very

masculine facial features) - - - I feared the highly publicized

controversy would cause me to be scrutinized more closely by

colleagues, and that I might possibly be outed then too - - that

didn't happen, but my old fears were surfaced again and held

me back from being more "out front" and in the public

eye as my VLSI work became successful several years later - -

-

-

- - - - medical progress continued, and by

1979 Stanford had developed the protocols that have been used

to this day for TS case management and gatekeeping to SRS - -

By the late '80's, the numbers of cases being processed in the

U.S. rose up to its current, ongoing level of about 1500 cases

per year going through MtF SRS. Perhaps another 500 or so go

outside the U.S. for their surgery. That's a tiny number when

spread around such a large country; however, it's still a lot

of people who must undergo a frightening, painful and often desperate

struggle to have any chance at a real life.

-

- By the year 2000, there were approximately

60,000 people in the U.S. who had undergone SRS (MtF or FtM).

The vast majority were in stealth in their new lives, and simply

blend in unnoticed among the rest of society.

-

-

- - - - now I had a very important decision to make - - - should

I take the offer from Fairchild to do their next microprocessor

architecture? Or join Xerox in Palo Alto to do research on special

purpose architectures for image processing? - - - so many factors

were in play in this decision - - - both seemed like outstanding

opportunities - - - but the desire to work in an exciting, creative

research environment again, as I had at IBM-ACS, finally drew

me to Xerox - -

-

- - - - there had been big turning points in my life before

- - and here was another one - - I faced a decision point - -

- going from a place of comfortable career success and an increasingly

active, happy social life - - to dropping into the intellectual

supercooker that was Xerox PARC - - a place of unlimited possibilities

for creative expression - - - but at a price of all-consuming

work for quite a few years - -

-

- - - - it's hard to say whether the eventual price was too

high, or not - - shouldn't I have stepped back, and considered

more closely all the wonderful new alternatives that were now

fully open to me in life? - - - why did I only consider the two

major career opportunities? - - -

-

- - - - was it fear of financial insecurity? - - - this had

been a big source of anxiety all during my transition, because

of the huge unreimbursed medical expenses and also the expenses

for supporting Kelly and Tracy - - -

-

- - - - or was it a lack of confidence in the future for my

personal life? - - - although I was feeling really good about

myself and enjoying life - - - I had a growing realization that

while some men liked to date and enjoy intimate fun with transsexual

women, who are often very passionate partners, few men would

knowingly take a TS woman for a wife due to social stigmatization

- - -

-

- - - - I'd begun to worry that although I could have a fun

social life and sex life, I might not be able find a mate to

share life with - - - I'd learned that once you were emotionally

involved with someone, in fairness you had to tell them about

the past - - and in most cases you'd then either lose them or

the relationship would shift into a different and less-serious

phase - - after having this happens to you several times, you

can get a bit burned out and tend to give up on love and just

settle for less meaningful affairs with men who "don't know"

- - - this has always been a big quandary for TS women (although

things gradually became a lot better by the 90's as the condition

became less stigmatized) - - -

-

- - - - or was it a kind of overcompensation, the need to make

enough contributions to society to counterbalance in the minds

of others their potential reactions to my past? - - - such overcompensation

is common among post-op TS's - - - a lingering result of very

low self-esteem, in spite of any later successes, going all the

way back to the humiliation and derision I faced in my early

years right on thru to my firing by IBM - - -

-

- - - - or was making creative contributions a substitute for

being unable to bear children (this is a sensitive topic that

I don't like to dwell on - - to this day it can bring tears -

- especially because of the forced loss of all contact with little

Kelly and Tracy, who had seemed like my own babies to me at the

time of my transition) - - -

-

- - - - or was it that, in addition to everything else, I had

a wild passion for the life of the creative mind too? - - - who

knows - - but the decision was made, and on I went to the Xerox Palo Alto

Research Center - - - and a period of intense focus on my

research career - - -

-

- [return to Contents]

-

-

- 6. XEROX

PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER (PARC)

-

- The SIERRA Project

-

- At Xerox, I initially reported to Mike Wilmer, in PARC's

Systems Sciences Laboratory (SSL), to work on a special purpose

system architecture for image processing - - the target application

was to try to create a compound OCR/FAX system - - - the "Sierra

project" - - - I innovated a cool, though on reflection

somewhat bizarre, architecture for this system - - -

-

- - - - after considerable toying around with various image

processing variants - - - Jorge Hernandez and I design and build

a particular hardware prototype - - I conduct extensive simulation

explorations of the OCR methods in parallel with hardware design

- - we get the thing running - - it really works! - - and in

later retrospect, I gained many important meta-architectural

insights from this experience - -

-

- - - - but we began to take flak from folks in the Computer

Science lab (CSL), who sniped at this project for being too complex

and costly - - - I don't think the presentations I gave about

Sierra in "Dealer" were very effective either, and

that didn't help - - I was still shy enough to get a bit sweaty,

and verbally hesitant, when talking in front of a group - - I

was in awe of what the CSL team had accomplished with the Alto

and the new form of distributed computing environment at PARC

- - - under the visionary leadership of Bob

Taylor - - - I hoped to get their respect - - but it wasn't

to be based on Sierra - - - it was gradually dawning on me too

that even with major re-engineering, any Sierra product prototypes

would be way too costly at the time - - -

-

- - - - about this time, in late '74 or early '75, we got a

new lab manager in SSL - - - his name was Bert

Sutherland - - - I recall a critical meeting with Bert, where

I presented the Sierra architecture to him and to his consultant,

the famous computer architect Wes

Clark - - - my impression was that Bert and Wes thought I'd

done some interesting (and certainly different!) architectural

work - - - hmm, would this mean that Sierra could continue? -

- -

-

- - - - I was pretty happy about how things were going for

me outside of work at the time - - - I'd was doing lots of fun

things, including making backpack trips to the Sierra Nevada

again - - -

-

- - - - I found that it was easy to meet some nice guys by

getting involved again in hiking and backpacking - - - it was

a great way to go on long dates and have something special to

share with your partner - - - and since there were more guys

than gals involved in those sports back then, it helped improve

the odds of meeting someone nice - - -

-

- - - - I was hoping to continue combining a fun personal life

with reasonable career success at Xerox - - - but the Sierra

project at Xerox was just too great a technical reach at the

time to be commercially feasible, given the low density and high

cost of the many components it would take to build it - - - and

it wasn't long before Bert canceled the project! - -

-

-

- Lynn in 1975, on a backpacking

trip to the Sierra Nevada with a boyfriend,

- gets ready for a day of hiking

and peak climbing (shown here near Ragged Peak).

|

|

|

-

-

- Lynn at a tent site on the approach

to Mount Ritter and Banner Peak,

- while on another backpack trip

with a boyfriend, in 1975.

-

-

- SIERRA Aftermath

-

- - - - this cancellation of Sierra was very unsettling - -

as a system architect and designer this was the third major project

canceled out from under me - - also, I wasn't sure how to save

my image within the competitive PARC environment - - - given

this "failure", I figured I was probably doomed to

be an underdog there - - -

- - - - about this time, I had moved in order to be closer

to Xerox PARC. I'd been driving my 240Z on mostly windy back

roads from Los Gatos to Palo Alto to get to work, and although

it was a fun drive, it was very time-consuming. With a now-secure

position, I was able to afford a nice little home at 1538

Winding Way in Belmont, CA. It was high on a hill overlooking

the bay - - - and the drive to PARC was shorter and was against

the main traffic and thus a lot easier - - - this would turn

out to be my cozy home during the period of intense work ahead

at PARC - - - although right now I worried that this would be

a repeat of my experience at Memorex, where I'd just bought a

condo and then changed jobs to a location a lot further away

- - -

-

- - - what a roller-coaster ride - - I was feeling pretty low

about my work right now - - although in retrospect this was,

and still is, a very common experience for high-tech workers

in Silicon Valley, so I shouldn't have taken it so hard - - many

folks spend their entire careers there, and never really "pick

a winner" - - never become part of a really successful project

that makes it to market and succeeds there - - -

-

- - - however, I couldn't have guessed what an incredible intellectual

adventure was just around the corner - - and what a great research

leader and wonderful personal mentor Bert Sutherland would turn

out to be - - -

-

- - - - I owe Bert Sutherland so much for everything I've accomplished

since then - - -

-

- - - Bert introduced me and my PARC colleague Doug Fairbairn

to his brother Ivan

Sutherland, and to Carver

Mead, at Caltech - - Ivan and Carver were investigating the

longer-term potential of MOS-LSI - - - Carver had a device physics

background, and had done extremely important theoretical work

on determining the likely fundamental gate size limits for MOSFETs

- - his theoretical lower limits were amazingly small - - Ivan

had estimated and articulated the possible opportunity space

that such limits opened up for computer system designers - -

but also, given his deep background in system design, computer

graphics and CAD, Ivan raised the key question of how would architects

cope with the complexity of such very large scale designs - -

-

- Formation of the VLSI System

Design Area at PARC

-

- Doug and I team up - - as Bert Sutherland then forms the

new "LSI Systems Area" (later to be called the VLSI

Design Area) in his lab to "explore LSI design methods and

tools" - - this was a big step for me, as I became responsible

as Area Manager - - gads, was I really ready for this? - - -

I begin recruiting - - and Doug and I begin lots of interactions

with Carver and his students - - -

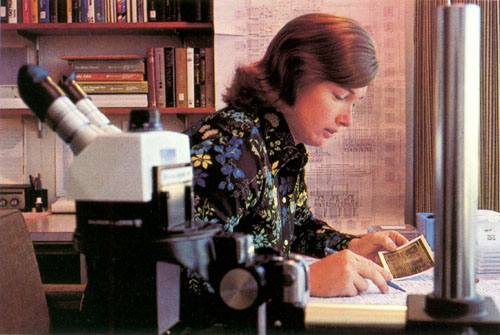

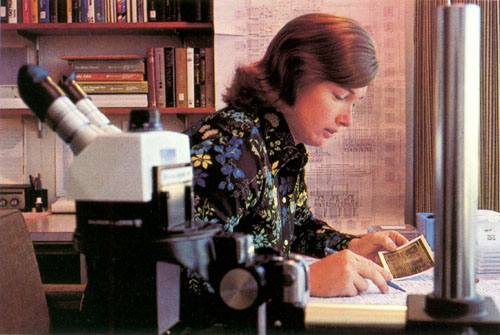

Photo of Lynn in her office at PARC (1977)

-

- - - - Carver had important Intel connections, having been

a consultant there since the early 70's - - and based on his

Intel experiences, he began teaching courses at Caltech on the

then current Intel methods for MOS-LSI circuit and layout design,

including examples of ALU designs, etc., the sort of designs

actually being used in the new Intel microprocessors - -

-

- - - - Carver's courses were totally unique at the time -

- there were no other university course anywhere that taught

students how to implement this level of logical functions into

MOS-LSI layouts - - - Carver also had access to Intel's and other's

fab lines, where occasional "test chips" could be dropped

in for processing, so some student projects could occasionally

be fabricated - - - but even though his students did more of

the overall design themselves - - and thus were often more efficient

in prototype design productions than existing industry teams

- - - Carver could see that no knowledge then existed to deal

with the eventual complexity of designs as chip technology moved

towards his theorized ultimate limits of density - -

-

- - - - Doug and I learn about all this stuff from Carver -

- and do some preliminary LSI chip designs ourselves - - - Carver

was a real character, very charismatic, and very passionate about

the potential of MOS-LSI - - he wanted to get more system designers

interested in it, especially given the work he'd done with Ivan

that revealed the eventual potential of the technology - - he

just didn't understand why there wasn't more support for research

into the design aspects of LSI - - - so he became very excited

by our enthusiasm as we got more involved - - he was also wowed

by the amazing computing environment at PARC (the Alto's, ethernet,

laser printers, etc.) and the possibilities that this then-unique

environment presented - -

-

- - - it seems strange now that almost no computer architects

had paid any attention to Carver before - - perhaps the idea

of working at the layout level, or even having to know anything

about layouts, seemed beneath most architects - - this may have

been a combination of looking down on the slowness of MOS technologies

vs the bipolar ECL technologies, and a holdover effect from the

old pMOS metal gate days, when "only peons worked on layouts",

cutting rubies, etc. - - - "after all, the architect could

just hand-off an RTL-level design to be implemented into logic,

and the rest was all optimizeable at each level by the different

specialists, wasn't it?" - - -

-

- - - - how could these architects have known that by exploiting

Robert

Bower's invention of the self-aligned gate and the new ion-implantation

techniques, the emerging nMOS (and later CMOS) technology was

now a totally different beast, and full of architectural promise

- - especially since it got faster and faster as it scaled down

towards the limits that Carver had calculated - - -

-

- - - in contrast, Doug and I had no such past preconceptions

against learning about the details of MOS technology and circuit

layout - - we were just so amazed to be able to get at MOS-LSI,

and design things in it, that we jumped in and learned about

it as fast as we could - - from Carver, from his students, from

taking short courses in all sorts of related areas (such two

or three day "intensives" were a key method for knowledge

transfer in the Valley in those days) - - - ( one of these courses

was an intensive on charge transfer devices given by Carlo Sequin,

a CCD pioneer from Bell Labs who'd just joined the faculty at

U. C. Berkely - - Carlo turned out to be an important partner

in our later efforts ) - - - and we learned quickly by doing

more and more design ourselves - -

-

- - - - with Bert's encouragement, Doug and Jim Rowson, one

of Carver's students, began work on the design and programming

of a graphical LSI layout system on the Xerox Alto - - this creation

of new forms of software tools for the Alto became the early

important rationale within Xerox PARC for the LSI Systems Area's

research - - this long served as a "cover story" -

- and was, for example, sort of tolerated by CSL (we were finding

new uses for the Alto) - - even as our work later expanded out,

bootstrapping to impact the wider arena - -

-

- - - - having designed digital logic in everything from relays,

to vacuum tubes, to discrete transistors, to SSI, to MSI-TTL,

the move to MOS design was yet another familiar technology transition

exercise for me - - probably like learing a new language for

some folks - - and, being experienced at multiple levels of design

(physical, circuit, logic, architecture), I studied hard to understand

those levels in nMOS-LSI too - -

-

- - - curiously, there also seemed to be a lot going on in

the Intel designs that wasn't directly stratified in traditional

architectural, logic, circuit and layout levels of design - -

- this reminded me of ACS, where much of the actual knowledge

at the hybridized interfaces of architecture, logic-design and

circuit design were not formally codified in current "texts"

- - this further complicated things - - there were a lot of hybrid

structures reminiscent of the relay switching circuits I'd studied

in Caldwell's book on "Switching Circuits and Logical Design"

at Columbia - - - was there some way to taxonomize, classify,

exploit and simplify all this stuff? - -

-

- The idea of "designing

design methods": the Mead-Conway collaboration

- - - then, reflecting on my earlier ACS design process efforts,

I began to sense some very weird possibilities - - - given Carver's

theories about the ultimate scaling limits - - perhaps MOS-LSI

really could open up the room for system architects to finally

realize their "architectural dreams" - - not just the

usual workstation or minicomputer scale of machines - - - but

for grand things like I'd experienced in the superscalar and

image processing architectures - - and actually get them economically

implemented - - but this could only happen if more digital

system architects knew how to think about designing in that medium

- - and had a faster, less expensive way to do it than to

involve an entire team of specialists (i.e., logic designers,

circuit designers, layout designers, process designers) for each

chip design - -

-

- - - - again, recalling my logic design standardization effort

at ACS, and the "designing the ACS design process"

proposal - - where I had viewed a "design level" as

subject to redesign, even to rather significant paradigmatic

change - - I began to recall and reflect on the Steinmetz and

Shannon precedents - -

-

- - - - especially Charles Steinmetz,

who was one of my true long-time heroes - - the immigrant and

social underdog - - - who, in spite of a major physical handicap,

rose to technical prominence at the great General Electric Company

- - who single-handedly had generated, shaped and channeled knowledge

about AC phenomena, via his symbolic mathematical methods, so

that the average engineer could work with AC - - his methods,

taught at Union College, in Schenectady, NY were largely responsible

for a huge wave of progress in the electrical industry - - it

seemed as if we were now at the threshold of something similar,

a similar opportunity and challenge - -

-

- - - - reflecting on that past history - - - and on how Carver

had been trying to proselytize current expert architects into

becoming LSI practitioners "by example", i.e., by using

existing, evolving methods, and creating examples of new, rather

clean architectures quickly designed by small teams - - I just

didn't see how that form of proselytizing would work - - - it

would only impact in an ad-hoc manner over a long period of time

- -

-

- - - - not only that, but I think we all intuitively perceived

that many more possible system architectures could be created

and be cost-effective in MOS-LSI than previously thought - -

- thus it would take many, many more architects to explore and

do this all this new stuff - -

-

- - - - so we couldn't rely on existing"advanced computer

architects" - - but needed lots more "regular digital

system designers" for all kinds of new systems in VLSI -

- so it didn't make sense to try to just win over existing architects

to do LSI - - - there wouldn't be enough of them - - somehow

what was needed were methods to create lots of new system architects

- - from scratch - - so, again, the Steinmetz story comes to

mind - -

-

- - - - I suggested to Carver that we deliberately design new,

simplified MOS-LSI design methods, deliberately aimed at

not just the current expert digital system architect - - but

more directly at even the "budding, novice architect"

- - making it so easy to get started that more of them would

try it, and work from architecture all the way to the layout

level - - Carver later coined the term "the tall thin person"

for this "new type of VLSI system designer" - - - Doug

and Jim could help forge new computer-aided design tools to support

this new sort of designer - -

-

- - - my idea was to deliberately distill and recompose from

all available nMOS logic, circuit and layout design methods the

simplest hybridized methods possible that would let a digital

system architect (for example, a Conway) jump right in and do

a whole system design from top to bottom - - i.e., the sort of

thing that folks like Lynn Conway would really liked to have

learned back when she first heard about the 4004 - - -

-

- - - - and also to adjust various viewpoints about "just

what a chip design was" - - getting it into 2-D overview

needed for the architect, rather than always focusing on 3-D

cross-sections for circuit details, and non-topologically-relevant

logic-gate diagrams traditionally used for logic design - - when

shifting from bipolar to MOS technologies, we could bring back

echoes of useful design thought-styles from relay switching-circuits

and vacuum tube circuits - - simplifying ideas - -

-

- - - thus a shared vision began to develop in our team - -

not just Carver's original "theory about eventual ultimate

limits" and "the challenge of complexity" - -

but my vision and approach on how to "deal with complexity

through deliberate methodological simplifications" - - -

and my concepts of how to craft simplifications that had a good

impedance match with the knowledge base of the average digital

designer of that time - - - we would create a new "VLSI

design methodology" - - -

-

|

- One of the great heroes of the

early days

- of electrical engineering:

-

- Charles

Steinmetz

-

- His development of

- a symbolic method of calculating

- alternating current (AC) phenomena,

- simplified an extremely complicated

field, understood by few,

- so that the average engineer

- could work with AC.

-

- This accomplishment was largely

- responsible for the rapid progress

- made in the commercial

- introduction of AC apparatus.

|

-

- - - - well, just what did this VLSI design methodology begin

to consist of? - - - my idea was to initially only teach potential

designers about a very small key subset of available LSI

logic, circuit and layout methods - - - a key subset that would

cover the design of any digital system or computing structure

- - - a key subset that was internally simple, elegant, and easy

to teach to the existing digital design community - - -

-

- - - - we would use only simple two-phase clocking - - - use

simple dynamic registers - - - teach basics at the circuit level

to enable transistor ratio calculations, delay calculations,

establish fan-out rules, driving of large loads, etc. - - exploit

pass-gate logic in various classic architectural building-blocks

- - - use PLA's for any messy logic and for control logic - -

- use "stick diagrams" for initial system cells to

layout conceptual designs - - establish system-level structures

of register to register data paths, often with pass-gate logic

between register arrays - - with control lines perpendicular

to the data paths - - current density limitations - - power calculations

- -

-

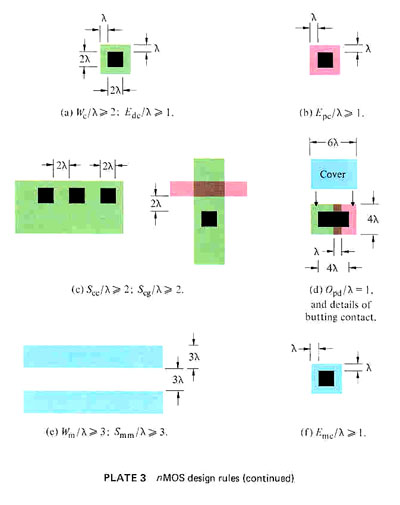

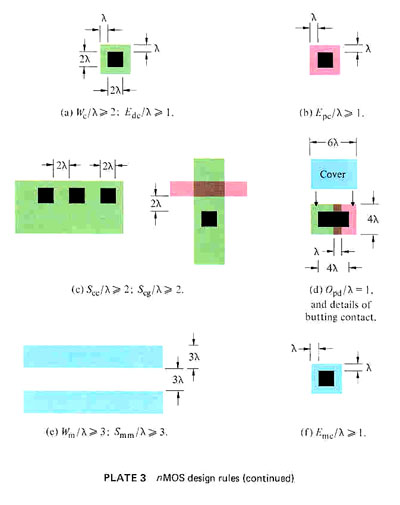

- The innovation of scalable design

rules, based on the length-unit "λ":

-

- - - thinking about stick diagrams - - I pondered the difficulty

and computational complexity of trying to instantiate layouts

using typical layout design rules - - this was especially a problem

when using personal workstation-based graphics-layout tools like

Icarus - - - then I hit on the idea of using simple, scalable

design rules - - these became known as the so-called "lambda

rules" - - - this innovation greatly simplified the conceptualization

of chip layouts - - - and also dramatically reduced the computational

complexity of the layout descriptions - - -

-

- - - - Carver really liked the scalable design rules idea

- - - he helped refine some line width and spacing ratios, based

on estimates of future nMOS process evolution - - to make the

rules a bit more optimal and hopefully more "acceptable"

- - - we ended up with a just two pages of very basic, easy to

understand design rules, whereas most processes had about 30

pages with all sorts of arcane stuff in them - -

-

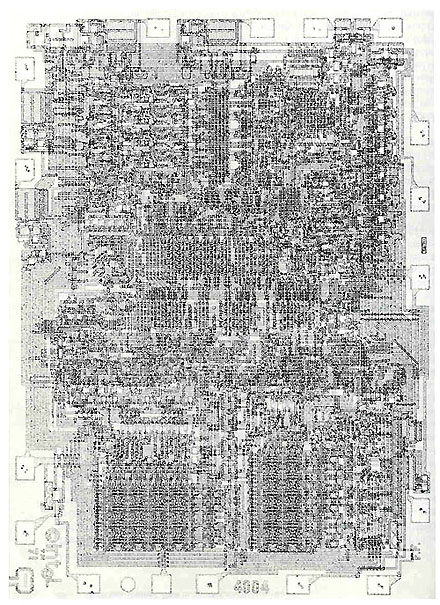

|

Plate 2. Mead-Conway Scalable

nMOS Layout Design Rules |

|

-

-

|

Plate 3. Mead-Conway Scalable

nMOS Layout Design Rules (cont.) |

|

-

- - - - however, these "non-optimal" rules later

became very controversial, and caused considerable backlash from

establishment figures who didn't seem to recognize the issues

of computational complexity, teachability, and time-to-design

tradeoffs that we were concentrating on - - designs created under

these rules looked so "clean and simple" that they

at first looked like "toys" to establishment folks

who didn't understand what we were doing - - - interestingly,

the rules gave up much less in area than most critics initially

guessed - -

-

- - - but the new design rules also opened up an important

new opportunity - - we could get access to various fab lines

by varying only one basic parameter, the length unit lambda,

for a given layout design - - we all worked to tabulate and simplify

the other factors at the fab line interface - - - and Carver

went on a quest to interact with all his contacts to set up cleaner

interfaces to a number of different fab lines, so as to increase

the opportunities for finding fab for student projects - -

-

- Carver coins the term "silicon foundry" to

promote clean interfaces with maskmakers and fab lines:

-

- - - - Carver coined the term "silicon foundry" for a line

that can be accessed in the new "clean way", i.e.,

simple logistical interface, standard ways to prescribe mask

polarities and alignment marks, simple scaling of the lambda

design rules, etc.- - and importantly, one definitely need not

jointly design and spec a process for each particular chip design

- -

-

- - - - the term foundry later became very controversial -

- - it really bugged lots of people, who didn't like it's apparent

dethroning of fab as the end-all, be-all of chipmaking - - (note:

the term is now in everyday use in the semiconductor industry)

- - Carver had a way of bringing notice to himself and

to our work by confronting traditionalists with what seemed

to be rather outrageous claims, and with inventive, but slightly

offensive, new terminology! - - Carver was always memorable!

- - -

-

- - - - Mead's growing interest in VLSI computer architecture:

It's interesting, given his background in device physics and

circuit design, Carver became extremely interested in computer

architecture, and wanted to "do it" himself - - - whereas

I, with my background in computer architecture, became extremely

interested in meta-architectural issues of selecting and reconstructing

the lower-level and mid-level zones of VLSI design to make them

into a "kit of parts that was more accessible to architects"

- - - we both seemed to want to learn and master what we already

didn't know much about - - to each of us the other area "seemed

cooler", at the time - -

-

- - - - therefore, in parallel with my obsessing on the design

methods at PARC, Carver focused intense energy on the architecture

and design of LSI microprocessors, the so-called "OM machines",

at Caltech - - - collaborating with his student Dave Johannsen

- - on a new machine, the OM-2 - - - OM-2 was just starting up

just as we finalized details of the design methodology - - -

Carver and Dave and several other students carried out the design

- -

-

- - - - fortunately, Carver was able to impose the new design

methodology being worked out at PARC on the OM-2 - - as a result,

the OM2 and all its detailed subsystems later became usable as

the classic microprocessor design example for Mead-Conway text

- - - somehow when conveying the methods to the OM2 team, Carver

didn't mention they were my idea - - - and when I visited Caltech

later, OM2 team members excitedly told me how they were using

"Carver design rules" as though I'd never heard about

them, much less invented them - - -

-

- - - - this caused a big flap between Carver and me, but didn't

resolve the issue - - - and "who was I" anyways - -

and we entered a phase where I got innovative ideas

and "worked them up in the back room" while he played

famous professor out on the public stage flaming about our results

- - - it was actually OK in a way - - after all, he was already famous,

knew tons of key people and could open any door - - - while I was less credentialed and had "a past" that needed

to be closely guarded - - - we were uneasy but incredibly productive collaborators,

each playing our respective roles in doing amazing things we couldn't have done otherwise - -

-

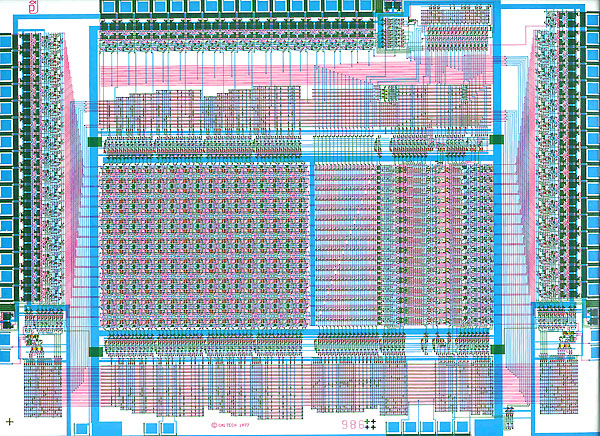

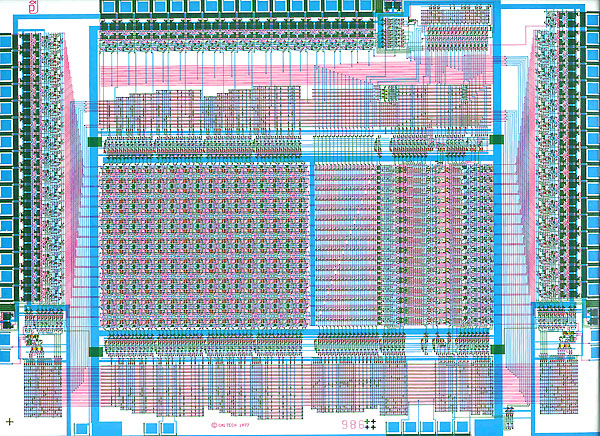

- The OM2: A microprocessor data

path designed using the Mead-Conway methods and layout design

rules

|

|

-

- - - discuss the concepts of cells and subsystems - - - the

new intermediate level of architectural building blocks - - thinking

back to ACS and Sierra - - moving up from gates and F/F's - -

- to subsystems instantiated in 2-D from cells - - -

-

- - - - meantime, Doug Fairbairn and Jim Rowson got the ICARUS

layout system running on the Xerox ALTO workstations - - it was

simple in structure, very fast and quite effective - - it exploited

the newly simplified design methodology - - they created a tutorial

on how it was put together - - it is now clear that their pioneering

work on ICARUS ultimately triggered the evolution of a whole

range of new forms of CAD tools - - setting the EDA industry

off into an entirely new direction - -

-

- But then, what to do with

"the methods"?

-

- - - - then all of a sudden, a remarkable transition occurred

- - - going over and over the simple collection of methods we

now mainly used for most designs - - and bit by bit compressing

the amount of material needed - - - I realized that "wow,

we've got it", i.e., we really had figured out and proven

out in a major design trial an extremely simple, but fully workable,

covering methodology adequate for nMOS digital system design

- - - this was no longer just a dream, a vision that we were

passionately pursuing - - we'd actually got it! - - -

-

- - - -ah, but now we had a completely new kind of problem

- - - what the heck could we do with all this stuff - - this

tiny group of collaborators at PARC and Caltech - - - should

we write papers? - - - but who'd ever publish them? - -

-

- - - - I mentally wrestled with this frustrating problem -

- I could see the reactions to any claims we might make - - after

all, "who were we" - - - or more particularly, "who

was Lynn Conway, this woman who only had an MSEE and who no one

had ever heard of before, to be telling the industry how to do

digital electronics design?" - - - the situation required

that we come up with some "very strong methods" for

even getting our results in front of folks for widespread evaluation

- - much less into acceptance, and use - - - I reflected again

on the past and looked for analogous situations - - and recalled

Steinmetz' propagation of the symbolic methods in courses at

Union College - - I thought a lot about what had happened there

- - -

-

- - - - and then I thought about Dr. Benjamin's 1966 paradigm-shifting

medical textbook - - - and how he had packaged a collection of

avant-garde but serious research results not into scattered journal

papers, but into a comprehensive, compelling, tutorial textbook

that had changed lots of minds about his ideas - - -

-

- A death in the family

-

- - - - in the middle of all the growing intellectual excitement

at work, I got an urgent phone call from my brother - - our mother

had suffered a sudden relapse of the lymphoma cancer she had

thought she'd licked years before - - she was in the hospital

in Austin, Texas, and wanted to see me - - he asked if I could

come down for a day to help cheer her up - - -

-

- - - - I'd seen my mother only a couple of times since my

transition - - - our relations were very strained, because she'd

never accepted my gender transformation - - - she just wouldn't

let go of her "son" and embrace her daughter - - -

no matter how much my physical appearance and outward personality

had morphed, she still managed to see the "old" me

in there somewhere, and she still made mistakes with pronouns

and with my first name - - - however, I went to Austin anyways,

out of concern for someone who was now possibly in deep trouble

- -

-

- - - - my brother met me at the airport and we went to the

hospital together - - - it was a tearful reunion, at least for

for my mother - - - she didn't look well, and she kept saying

"I'm frightened", over and over again - - - there wasn't

much I could say, though I tried to calm her - - - it quickly

became clear that this was not a cheer-up visit; this was to

be the last time I'd see her alive - -

-

- Lynn in 1977

-

-

- - - - at one point she began looking at me very carefully

- - right in the face and eyes - - I was a bit surprised, because

she would never really look right at me during our earlier meetings

- - then after a while, she said "you're beautiful, so beautiful",

with kind of a quizzical, questioning feeling to it - - - I wondered

what the heck she meant by that! - - - was she finally waking

up to the fact that something truly profound had happened to

me nine years ago? - - - and that it wasn't realistic to keep

thinking that she had two sons anymore, but had a son and a daughter

instead? - - who knows - - -

-

- - - - after I'd been there quite a while, I noticed there

hadn't been any other visitors - - that seemed strange since

we had lots of relatives living in the area - - - I asked my

brother about it and found out why - - - my mother had warned

them all that this was the day "I" would be there,

so that they could avoid the terrible embarrassment of "having

to see Robert dressed as a woman" - - -

-

- - - - I'm not sure what they expected would embarrass them

so - - it reminded me of the way the senior execs at IBM had

reacted - - - namely, to an imagined stereotype, rather than

to a real human being who was actually a rather nice person if

you took the time to get to know her - - -

-

- - - when it came time to leave and say our goodbye's - -

my mother said "please, please stay, I'm so afraid"

- - I said that I was sorry, but I had to go - - - that I had

a plane to catch - - I told a small white lie, saying that maybe

I could fly back again soon - - but of course that wouldn't happen,

since all the others would be there till the end came - - - as

it did a few days later - - - and I wasn't invited to the funeral

.

-

- - - - I was so used to such treatment by this time that none

of it caused any emotional stir in me - - no shame, no hurt,

no anger, no tears, no nothing - - - it was as if I were watching

a familiar movie scene - - - the unfolding scene became just

more "ethnographic data" to be filed and referenced

at a later time - - - yet another record of oft-encountered "transphobic"

behaviors - - - I felt like an observer of events that I wasn't

even personally involved in, and was just going through the motions

- - -

-

- - - - This notion that "It's all just data" - -

- that all these behaviors and interactions were useful things

to document as ethnographic data about gender transitions - -

- made events that would otherwise felt very hurtful seem to

be "interesting observations" instead - - - there was

no need to assign blame for what happened one way or the other

- - - these were all just "natural side-effects of a gender

transition" - - -

-

- - - - this way of looking at things came from my studies

in anthropology - - - I began to feel that maybe all these "observations"

would prove useful someday - - - in the meantime, this mental

trick proved very useful in easing the natural pain I felt in

such situations - - -

-

- - - - Anyways, I'd already lost my mother when I was four

years old - - -

-

-

- The idea of writing "the

book"

-

- - - - in a meeting at PARC with Carver, Doug, Jim and few

other folks in the late spring of '77, it was late in the day;

we were tired, and kidding around and winding things down - -

I had finally hit on a specific idea, and I just said it out

loud: "Let's write a book on the new methods!" - -

- "a book that looks like the kind of textbook you might

see after such methods had been used for many years and were

all proven out in practice - - full of design examples, etc."

- - to my surprise, Carver instantly said "Yeah!",

very, very loudly - - and that was it: we set off to do "The

Book" - - thus another of "Lynn's wild projects"

was about to take off - - -

-

- - - during the summer of '77 and on into early '78 Lynn,

Carver, Doug, Jim, Bob

Sproull, Dick

Lyon, and Carlo

Sequin all teamed up to help brainstorm about, create and

test this book - - this was an incredibly talented set of folks,

and we really infected each other with our mutual excitement

about the work - - - a series of versions were written and tried

in preliminary courses - - the first three chapters in a course

taught by Carlo at U.C. Berkeley - - then the first 5 chapters

(including the OM-2 design examples) in a course by Bob Sproull

at CMU - - - at this point we decided to change the title from

Introduction to LSI Systems to Introduction to VLSI

Systems - - just about that time I'd seen "VLSI"

as an acronym a couple of times in Electronics Magazine,

and thought it would add the right additional flair to the title

- - we still called my PARC group the LSI System Area for a while,

but we'd change that a bit later too - -

-

- - - I'd recruited Dick Lyon by then, and he began collaborating

with Bob Sproull to formally define the layout design interchange

format that came to be known as "CIF2.0" - - an extremely

critical element in establishing linkages among all the various

design and fabrication tools - - Dick is a brilliant and creative

researcher, and would go on to invent the optical mouse chip,

invent a complete bit-serial VLSI design methodology for signal

processing applications, extend the scalable design rules to

CMOS, etc., etc. - -

-

- - - we'd also recruited Barbara Baird, who had been the secretary

for the 7100 team at Memorex, to be the administrative assistant

in the new LSI Systems Area - - Barb would prove to be an absolutely

key member of the team during the critical periods ahead - -

-

- Our secret weapons: the Alto,

Ethernet, Laser Printers and Arpanet

-

- - - - our secret weapons in rapidly writing and evolving

the textbook were the Alto computers, laser printers, and Arpanet

access at PARC - - - I did most of the writing and editing of

the emerging text on my Alto - - receiving input from Carver

at Caltech re the OM-2 - - and exchanging drafts, doing editing,

and collaborating with an ever increasing number of contacts

at other places, using e-mail and file transfers via the Arpanet

- - this infrastructure: the Alto personal computers, ethernet

and laser printers at PARC, Arpanet, e-mail, etc., way back in

'77, was very similar in effectiveness to the modern PC's - -

and gave us an amazing ability to rapidly create, distribute

for checking, refine and self-publish drafts of the emerging

text - -

-

- - - - not only that, but the Alto's and the networks presented

a whole new opportunity - - we could organize a "VLSI team"

of collaborators from many different sites - - I'd greatly admired

the effectiveness of CSL's organizational methods (CSL was the

other PARC computer lab) - - - and CSL Lab Manager Bob Taylor's

amazing leadership ability - - - so I somewhat copied the "dealer"

style of CSL - - where folks collaborate and compete in a complex

"open participation" environment, where what counts

is getting something you're working on "get into" the

emerging technology system - - only our "VLSI dealer"

was realized via interactions out in the Arpanet - - on only

a modest scale at first - - but it quickly got bigger, and bigger

- - -

-

- - - there was also a strong techno-ideological component

to our work - - partly a version of the PARC ideology of wanting

to "bring computing to the people" - - everyone would

have their own - - here in our case, it was the notion of wanting

architects and designers to be brought out from under the dominance

of the fabrication technology and facilities - - make them "authors

and writers" who got their stuff "printed in silicon"

- - gaining visibility for the intellectual work of the architect

and designer - - heck, up to now, it seemed that most people

thought that the fab line "made the chip", i.e., was

the source of the intelligence in it - - that's like thinking

that the printing press writes the news articles!- - -

-

- - - - then too, Carver had caught entrepreneur's fever -

- he was always looking for opportunities to start companies

- - - it was becoming clear that a large space of possible start-ups

might be opening up here - - -

-

- - - all these dimensions of thought: our shared vision in

a tight knit team, our new methodological ideas, the wild new

infrastructure we could exploit, our interactions with a growing

team of outside collaborators, the entrepreneurial opportunities

- - all this became intellectually intoxicating - - -

-

- - - - so it was inevitable that we would proceed - - but

we were no longer in charge of this phenomenon, it was in charge

of us - - and it wasn't until years later that I would realize

the personal price I was to pay, physically and emotionally,

for 6 to 8 years lost to anything else but my career - - -

-

- The crash effort

to evolve and propagate the new methods

-

- - - - and thus began a crazy, intense period - - - "this

was it" - - the time to really crank up, and make hay -

- it was now or never - - - and most everything else in my life

ceased, except work - - -

-

- - - - for the next several years, I worked six or seven

days of the week, often for 12 to 16 hours a day - - at my Alto

- - writing, e-mailing, FTPing files, - - - getting up early,

drinking coffee all day - - going home late - - drinking some

wine to finally crash at night - - then back at it the next day

- - - day after day, month after month - - - (by 1980, this phase

had almost ruined my health) - - writing "the book"

- - - and coordinating activities in an ever-enlarging "VLSI

community" out in the network - - -

-

- - - in the spring of '78, Bert suggested an exciting, but

very challenging possibility - - he was on the visiting committee

of the EECS department at MIT - - he'd talked about the Mead-Conway

work with folks there - - he offered me a "sabbatical",

a chance to teach at MIT that next fall and introduce the new

methods there - -

-

- - - - I was very, very intimidated by this prospect due to

lingering shyness with groups of strangers, frequent difficulties

in public speaking, and concerns about being accepted by folks

at M.I.T. sight unseen - - plus my thoughts of M.I.T. were tinged

with deep emotions and powerful memories of my earlier transitional

experiences and romantic affairs while there - - - maybe I feared

that somehow I'd be "outed" there - - - who knows -

- -

-

- - - - but Bert finally convinced me that this was a truly

significant opportunity that could not be missed - - I realized

that this was the opportunity to create and prototype what could

become the standard modern form of VLSI design course, based

on the emerging Mead-Conway text - - I realized that I just had

to do it, no matter how frightened I was - - - somehow Bert seemed

to know just when to encourage me to take the next, just barely

do-able, adventurous step - -

-

- - - we made a crash effort that spring and summer to finish

a complete nine chapter draft of the text - - I put together

Chapter 6, Chuck Seitz

contributed Chapter 7, Chapter 8 was contributed by H.T.

Kung and Carver wrote up Chapter 9 - - we printed up and

bound many copies at PARC, including color plates run on the

new Xerox color copier at PARC - - wow, this thing was starting

to look pretty amazing! - -

-

- - - we'd recruited Alan Bell from BBN to join the LSI Systems

Area - - Alan was a very shy, but extremely brilliant computer

scientist - - we had a hard time convincing him to come to PARC

- - it was a big move for him from familiar territory - - but

he did, and immediately began to play a critical role in prototyping

and evolving infrastructure for supporting and coordinating the

work to be done at both MIT and at PARC regarding project implementation

- - -

-

- - - - our work had also come to the attention of Merrill

Brooksby, manager of CAD development at HP - - Merrill began

to help us coordinate explorations within HP for obtaining QTA

fab - - we got that all set for the fall, with HP benefiting

by being able to "look over our shoulders at what we were

doing" - - -

-

- - - - in mid August, 1978, I set out in my station wagon

from California, headed for M.I.T. in Cambridge, MA, loaded up

with boxes full of books, notes and equipment - - - (by the way,

I kept my 240Z till '83 - - using the station wagon for work,

and the 240Z for play!) - - -

-

- - - - I had a lot to think about during that drive - - here

I was returning after almost 20 years to my old M.I.T environment

where I'd tried to transition so long ago - - - but this time

I was coming as a woman and a faculty member - - - it was almost

too amazing - - - but it was scary too - - - there were many

questions - - - could I really do this? - - - Bert Sutherland

thought I could and that I had to do it - - - but I had in many

ways lived a kind-of insular and protected life at PARC - - always

among the same folks - - - and I was still very shy speaking

in front of groups - - - how could I get up the nerve to teach

and do it several times a week all semester? - - - and in a totally

new environment - - - I was also becoming increasingly worried

that my wider exposure in the research community would lead to

me being "outed" by somebody - - - and that I'd suddenly

lose everything I'd worked for all these years - - -

-

- - - - the saving thing was that I was "on a mission"

- - - the mission of proving-out the Mead-Conway methods and

the draft textbook to be published the next year - - - and once

launched on such a mission, fear wasn't likely to stop me - -

- so off I headed to M.I.T. - - -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-